DPI-AI Framework

Vision paper on Building AI-Ready Nations through Digital Public Infrastructure.

Executive Summary

This paper presents the DPI–AI Framework as a practical way to think about how artificial intelligence can be integrated into public digital systems through Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI). It is written at a moment when AI capabilities are advancing rapidly, while many governments are still grappling with fragmented systems, legacy architectures, and uneven institutional capacity. Rather than proposing AI as a standalone transformation, the paper explores how existing DPI foundations can provide structure and coherence for the use of AI in the public sector.

Many of the ideas discussed in this paper are not new. Modularity, shared services, workflow orchestration, and human oversight have long been part of public sector digital ambitions. What has changed is the maturity and accessibility of AI, combined with the attention it now receives from political leaders, institutions, and the market. This convergence creates pressure to adopt AI quickly, often before there is clarity on how it should interact with existing public systems. The paper responds to this gap by offering a framework that connects current AI developments with established DPI principles and architectures.

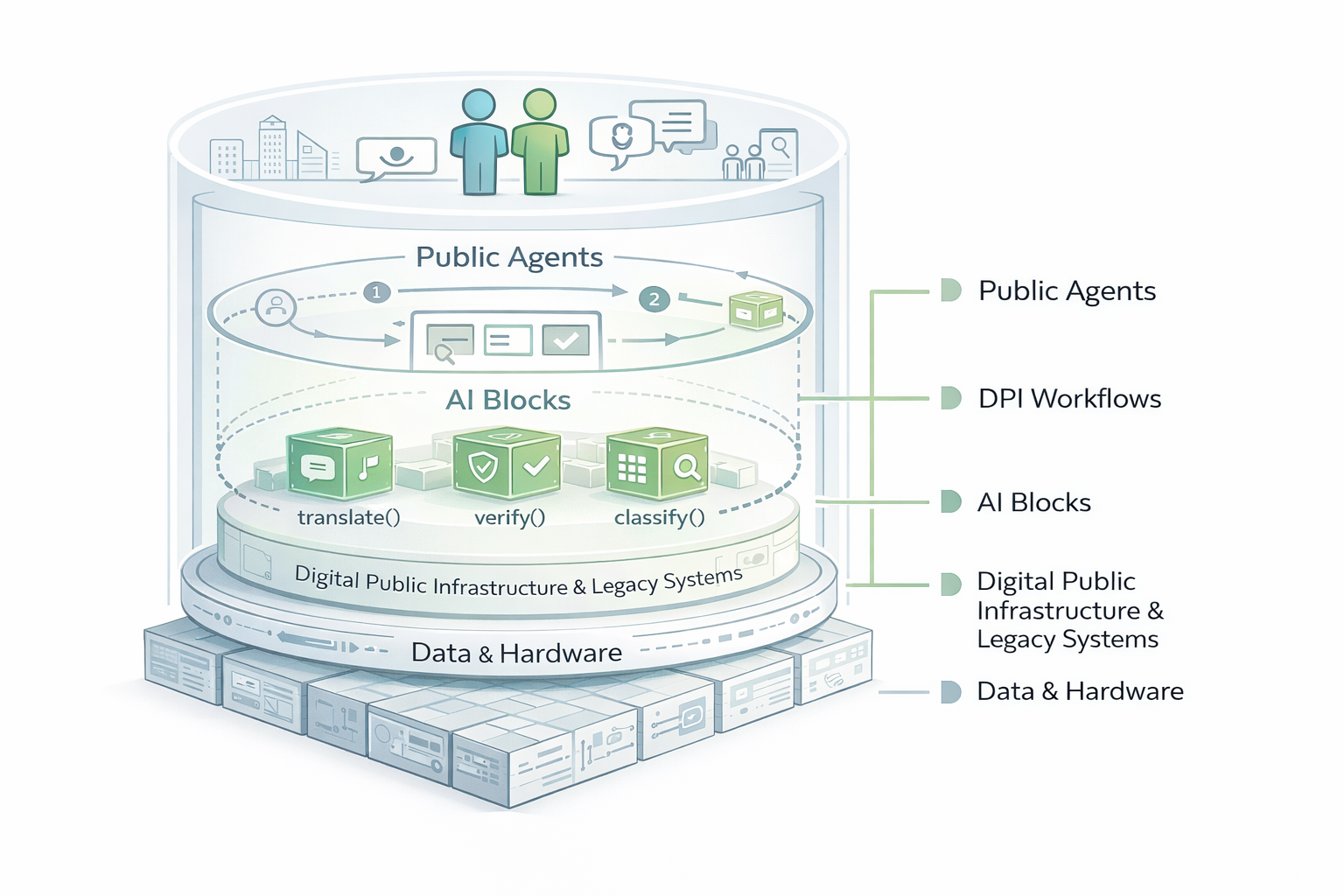

The DPI–AI Framework positions AI not as a new layer within DPI, but as an external and interoperable set of capabilities that connect to DPI through shared standards, governance mechanisms, and safeguards. It focuses on foundational DPI rails such as digital identity, data exchange, and payments. These foundations allow external AI systems to authenticate users and institutions, access authorised data, and operate across organisational boundaries, without being tightly coupled to specific applications or vendors.

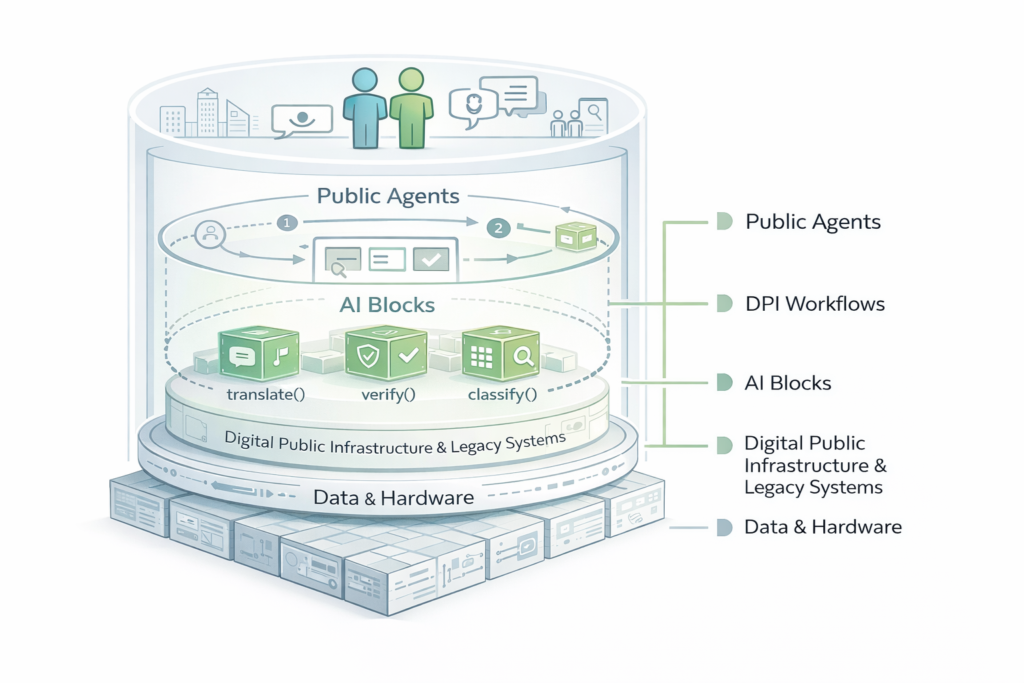

At the core of the framework are three interrelated elements that help translate this integration into practice.

AI Blocks are modular units of AI capability that can be invoked as callable functions. They are designed to perform both sector-specific functions, such as identity verification, registry creation, credential issuance, or decision support, and foundational, bounded tasks such as classification, summarisation, and translation. By treating AI capabilities as reusable building blocks, governments can adopt and evolve AI incrementally, replace models over time, and avoid embedding intelligence directly into monolithic systems.

DPI Workflows provide the orchestration layer that coordinates AI Blocks with existing DPI systems, policy rules, data flows, and human oversight. Workflows define how identity is verified, how data is accessed through data exchange mechanisms, and how AI outputs are applied within public processes. They make it possible to apply intelligence consistently across services and institutions, while maintaining clarity on responsibility and decision-making authority.

Public Agents are AI-enabled interfaces that interact with citizens and public servants. They draw on AI Blocks through DPI Workflows, while relying on digital identity for authentication, data exchange for authorised access to information, and payment systems where transactions are required. This separation allows experimentation and innovation at the interface level without compromising the integrity or governance of core public infrastructure.

Together, these elements describe how intelligence can be embedded into public service delivery while preserving interoperability, accountability, inclusion, and sovereignty. The framework deliberately avoids prescribing specific technologies or models. Instead, it offers a shared mental model that helps governments, development partners, and ecosystem actors reason about where AI fits within a DPI-based architecture.

The paper is intended for digital leaders in government, development partners, donors, and practitioners who are shaping national and global digital agendas, as well as for anyone interested in societal transformation, poverty alleviation, and developmental impact using technology.

Its aim is not to promote AI adoption for its own sake, but to provide a clear and practical way to align emerging AI capabilities with the foundational rails of DPI towards development outcomes, enabling more adaptive, coherent, and publicly governed digital systems over time. In this vision, the value of AI emerges not from its autonomy but from how it integrates dynamically with the foundational rails of DPI to create adaptive, intelligent, and publicly governed digital infrastructure.

Introduction

In a pivotal scene from the 1999 film The Matrix1, Neo, the protagonist, undergoes an instantaneous transformation. Seated in a chair, a diskette uploads knowledge directly into his brain. He opens his eyes and declares: “I know Kung Fu”. For a generation raised on the cusp of the internet revolution, this cinematic moment symbolized a dream of frictionless learning and limitless upgradeability.

Two decades later, the fantasy remains fiction. But we are indeed entering an era where advanced statistical models, particularly Agentic AI (based on Large and Small Language Models2), can assist in generating information, summarizing documents, responding to user input, and even tailoring services at scale. These systems, however, do not “understand,” “reason,” or “think” in the human sense. They operate by predicting patterns in data, not by grasping meaning or engaging in cognition.

There is no need for a new mental model for AI in government. The DPI approach is already set up to integrate AI, as long as we carefully consider safeguards, emphasizing cross-sectoral, governance, and procurement implications that are specific to AI. In other words, AI does not require a separate framework but rather adjustments within the existing DPI model. From this perspective, AI naturally fits as just another modular building block within DPI, reinforcing the principle of minimalism and reusability.

Why act now?

The cost of inaction is already visible. Governments that postpone building AI-ready digital infrastructure risk deepening dependency on proprietary systems and locking public functions into closed platform models whose costs increase over time. Without interoperable and publicly governed AI capabilities, ministries duplicate investments, procurement becomes fragmented, and crisis responses slow down. The greater cost, however, is institutional. When governments lack open and modular infrastructure, they lose the ability to choose their own digital paths, to adapt technology to local contexts, and to govern it on their own terms. Digital sovereignty is not achieved through isolation but through capability3. It depends on building the competence to design, reuse, maintain, and evolve shared public systems independently. Inaction preserves fragmentation and dependence. For example, in many governments a significant share of IT spending is devoted to maintaining duplicate systems that could be consolidated through interoperable services, with or without the use of AI. Proactive adoption of DPI principles, by contrast, builds resilience, reduces long-term costs, and strengthens autonomy through reuse, transparency, and national capability. Responsible AI adoption must also consider the environmental cost of training and operating large models, promoting efficiency and green infrastructure. For Asia and the Pacific, where digitalization remains uneven, inaction risks widening the digital divide and increasing dependency on global proprietary AI systems. Building interoperable, sovereign AI layers ensures that countries can retain control over data and technology choices.

This framework does not assume that AI should be prioritised ahead of foundational DPI work. In many contexts, the immediate focus remains on clean registries, reliable APIs, last-mile connectivity, and minimal institutional capacity. The purpose of the framework is to show how intelligence can be introduced incrementally once these foundations exist, without forcing a wholesale rebuild of public systems.

As these technologies evolve, it becomes useful to reconsider the nature of government itself. At its foundation, the government exists to deliver essential services that protect rights, meet obligations, and support people’s everyday needs. To do this reliably and at scale, governments depend on shared foundations such as records, laws, and regulations, which establish authority, define eligibility and entitlements, and ensure accountability.

From this perspective, government can be understood not only as a set of institutions or service channels, but also as an underlying infrastructure made up of reusable and rule-based functions. These functions operate across sectors and services, drawing on multiple sources of data while remaining anchored in public mandates and legal frameworks. Viewed this way, governmental functions resemble an interoperable system that can combine and orchestrate components to adapt to new needs and contexts, enabling a more agile, scalable, and people-centric model.

What is Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI)?

DPI4 is an approach to digitalization focused on creating foundational, digital building blocks designed for the public benefit. This approach combines open technology standards with robust governance frameworks to encourage private community innovation to address societal scale challenges such as financial inclusion, affordable healthcare, quality education, climate change, access to justice and beyond. It’s based on five technology architecture principles: 1) interoperability; 2) minimalist, reusable building blocks; 3) Diverse, inclusive innovation by the ecosystem; 4) a preference for remaining federated and decentralised (when possible); and 5) security & privacy by design.

At an implementation level, this approach takes shape through a set of foundational, interoperable building blocks5, such as (but not limited to) identifiers and registries; data sharing; AI/ML models; trust infra; discovery and fulfilment; and payments thatenable governments, private sector, and communities to interact and deliver services at population scale. Like roads or power grids in the physical world, DPI provides the shared rails that underpin digital inclusion, economic participation, and state capability. Countries6 like Argentina, India, Brazil, Singapore and Estonia have used DPI to expand access to banking, healthcare, education, and welfare systems, often leapfrogging traditional service models.

In many countries, the reality of digital transformation includes managing existing legacy systems. An AI-ready DPI approach does not require wholesale replacement of these infrastructures, there’s not enough money or time in the world to do that. Instead, it follows a “+1 approach”, enhancing what exists through interoperable APIs or DPI blocks that wrap around legacy systems. These small, modular updates allow legacy systems to actively participate in the DPI ecosystem, enabling data flows, orchestration, (and potential AI augmentation) without disrupting core operations. It ensures interoperability, data portability, and gradual modernization, transforming legacy assets into programmable, scalable components of a broader digital and AI-ready public infrastructure.

What is Artificial Intelligence in the public sector?

Artificial Intelligence (AI) refers to computer systems that learn from data and make context-based judgments to perform tasks such as understanding language, answering questions, executing tasks, recognizing patterns, solving problems or generating text or media. Unlike traditional software that follows fixed rules, AI systems adapt their outputs based on patterns learned during training and ongoing reinforcements. The most visible examples today are Large Language Models (LLMs), which are powerful models trained on vast amounts of data, and Small Language Models (SLMs), which are lighter and designed to run on smaller devices or at lower cost.

In government, AI can help public institutions work better by making services faster, analyzing information more effectively, and offering citizens more personalized and accessible support, while ensuring fairness and accountability. Equally important are fairness, explainability, and human oversight. Public sector early adoption of AI often begins with chatbots and virtual assistants that respond to citizen inquiries and has scaled to code or policy writing to enhance gov officials’ work. Without deeper reforms this can risk becoming “empty shelf AI”, tools that provide information but fail to deliver real services. To avoid this, AI tools need to be embedded into core government processes so that it contributes to measurable improvements in outcomes.

Many modern AI systems, including LLMs and SLMs, are trained on vast datasets collected from the public web and other sources where ownership, consent, and accuracy are not always clear. As these systems evolve, they increasingly depend on access to new types of data, including domain-specific, institutional, or even synthetic datasets. This makes data provenance, consent, legitimacy, and stewardship central to their responsible use within Digital Public Infrastructure.

In the DPI-AI Framework, this does not imply the creation of a new data layer, but rather the activation of the existing data infrastructure within DPI (Public datasets, registries, and consent mechanisms) as the foundation that allows AI systems to operate safely and transparently. Ensuring that the origin, governance, and permissible use of data are clearly defined is essential for trust, auditability, and compliance with national safeguards. Trained AI models, or “derived tools,” may also inherit risks, liabilities and biases from the data on which they were built. This reinforces the need for public oversight, ethical certification, and traceable data-to-model lineage.

Building on this foundation, the next layer of intelligence involves systems that can use this data responsibly to act on behalf of people and institutions. These systems are known as agents. An Agentic AI (Agent) is a system that uses AI, such as an LLM or SLM, not only to provide information but also to take action. Agents and assistants can connect with third-party systems to perform tasks, such as searching databases, submitting forms, scheduling appointments, or processing transactions. A chatbot or AI assistant is a type of agent that communicates with people in natural language, making it easier to interact with public services. Building on this idea, a Public Agent is an AI-powered assistant or agent integrated into government systems. Its role is to help citizens navigate rights, benefits, and obligations, while supporting governments in delivering services that are inclusive, transparent, and efficient.

Training language models and data governance

Every model learns from data7. Modern AI systems are not born intelligent; they are trained through exposure to vast collections of human-created information such as books, code, media, and public records. From these patterns, models learn to make judgments, predictions, and associations. In this sense, data is the cognitive layer of any AI system. For governments, deciding what data a model is trained on8, who governs it, and how it can be reused or corrected has become a new form of policy design.

Governments hold a unique advantage because they already produce and maintain large volumes of high-quality data that reflect public life. These include registries, legislation, court rulings, service records, research outputs, and cultural archives. Yet much of this information remains fragmented, unstructured, or locked within systems that were never designed for its data to be accessed for learning. The ability to process, structure, and govern this data responsibly will determine the success of AI in the public sector. A government cannot train a trustworthy model on unverified or ungoverned data.

Open and governed training data

Governments can strengthen trust in AI by developing structured repositories of high-quality public data that are ethically governed and accessible for research and innovation. These efforts help build sovereign cognitive capacity, allowing models to reflect national laws, languages, and social contexts rather than depend entirely on external or opaque sources. In practice, this does not imply training a single, general-purpose model on vast amounts of data, but often supporting many smaller, task-specific models that are trained or adapted for clearly defined public functions.

This distinction matters for scale. Training and maintaining large, multi-purpose models can require levels of computational infrastructure, expertise, and operational maturity comparable to those of major technology companies. By contrast, smaller models trained on well-scoped datasets can be more feasible for governments to govern, validate, update, and deploy, while still delivering meaningful public value. An ecosystem of interoperable models can also evolve over time without creating excessive dependency on any single system or provider.

Privacy and data protection remain central to this approach9. Training data must comply with existing legal safeguards and avoid including personal or sensitive information without consent. Once data is embedded in a trained model, it can be difficult to remove, correct, or fully understand how specific information influences outputs. Governments therefore need clear processes for oversight, privacy preservation, and accountability throughout the data lifecycle, including an explicit recognition that not all associations and correlations learned by AI systems are predictable or controllable.

This limited controllability cuts both ways. AI systems may surface patterns and relationships that humans would not easily detect, but they may also produce unintended or harmful inferences when trained on broad or poorly governed datasets. These risks reinforce the importance of carefully scoping training data, aligning models to specific purposes, and maintaining human and institutional oversight.

Establishing a strong foundation for public data governance is only the first step. Once data is responsibly managed and made interoperable, governments can begin to build intelligence on top of Digital Public Infrastructure. The DPI–AI Framework builds on this foundation by proposing an approach in which AI operates as an additional, modular layer that uses and extends existing DPI capabilities. In this model, interoperability enables reuse and coordination across systems, while governance and sovereignty ensure that AI remains aligned with public mandates, legal frameworks, and national context.

Bridging DPI and AI

The central challenge for governments10 today is not to recreate intelligence, but to design infrastructure that connects AI capabilities to public systems safely and equitably.

This paper proposes a practical path forward: building on top of existing DPI to create an AI-ready ecosystem. In this approach, DPI remains the trusted foundation while AI operates as an interoperable layer that uses this foundation to generate insights, support decisions, and enhance public service delivery.

The DPI-AI Framework defines this bridge between infrastructure and intelligence. It enables AI systems to plug into public digital rails through shared standards, safeguards, and transparent governance. By doing so, it extends DPI’s core principles of openness, inclusion, and accountability into the domain of AI, ensuring that intelligence serves the public purpose rather than private control. The DPI–AI Framework should be read as an extension of DPI logic into AI-enabled services, not as a parallel DPI model with technology-specific building blocks. Just as the internet became a public utility for information, AI is the cognitive utility but only if governments embed ethical, legal, and accountability frameworks into its design.

This is not a vision of sentient machines. It is a blueprint for augmenting state capacity: enabling governments to deliver adaptive services, orchestrate automation responsibly, and respond to citizen needs, rights and obligations with speed and accountability.

DPI-AI Framework

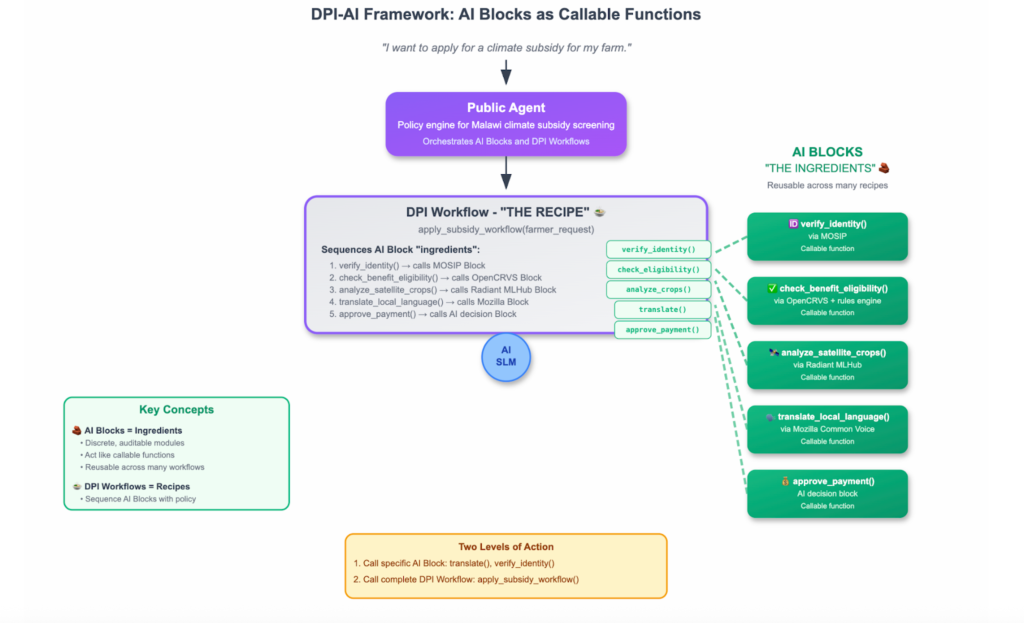

Imagine a farmer in Malawi applying for a climate subsidy. Today, this might involve filling out paper forms, waiting weeks for manual verification, and risking exclusion if records are incomplete. With an AI-ready DPI, the process looks very different.

A Public Agent, for instance a chatbot speaking in the farmer’s local language, guides the farmer through the application. The process is structured by a DPI Workflow, which acts like the recipe for delivering the subsidy. The workflow defines the sequence of steps, ensures each action follows policy, and coordinates all components involved. Within this recipe, the agent invokes AI Blocks as ingredients: one block checks eligibility against government registries, another translates dialect into structured digital text, and yet another verifies satellite imagery of crops. If the workflow encounters a problem, for example the farmer’s ID is unclear, it routes the case to a human caseworker agent for review11.

This scenario captures the essence of the DPI-AI Framework: a design approach that extends public sector capability by embedding modular and governable intelligence into digital public infrastructure.

The DPI-AI Framework is an architectural design approach that builds on the foundations of DPI by adding layers of intelligence that can be composed, audited, and reused across services.

The framework incorporates AI of different sizes and purposes: large foundation models, smaller task-specific Small Language Models, and other machine learning models for pattern recognition. By focusing on transparent and purposeful use, it ensures that AI remains aligned with public values and policy goals.

At the core of the framework are three key concepts: AI Blocks, DPI Workflows and Public Agents.

AI Blocks (or tool), a callable function that an Agent can use to perform a specific operation; are modular components that expose specific capabilities in a structured way. They are the ingredients that can be combined in different ways depending on the service being prepared. These capabilities may include interpreting policy logic, retrieving data, image recognition, generating content, translation, assisting classification, evaluating eligibility, or offering domain-specific insights. AI Blocks can be further classified into Foundational blocks and Sector Specific blocks. This layered view helps governments divide and conquer the complexity of AI adoption by separating common infrastructure from domain-specific intelligence. Finally, AI Blocks are not only governed components but can themselves be treated as Digital Public Goods12 when designed with open standards, transparent governance, and policy guardrails. Equally, existing DPGs can adapt into AI Blocks when augmented with callable intelligence that plugs directly into workflows.

DPI Workflows are the orchestration layer that turns AI Blocks into usable public services. If the blocks are ingredients, the workflow is the recipe that determines how and when they are used. A workflow defines how different blocks, data sources, and agents interact to complete a task. It structures the logic of delivery, ensures that every step follows policy, and makes the process auditable from end to end. A DPI Workflow can coordinate actions such as verifying identity, invoking AI Blocks, accessing registries, and triggering entitlements. It provides the structure that ensures AI is used purposefully and safely in service delivery.

Together, AI Blocks and DPI Workflows form the programmable core of the DPI-AI Framework. They allow governments to build modular intelligence into public AI systems through composable and governable functions that align with the principles of DPI.

Public Agents are users of this architecture framework. These agents are the frontline operators of workflows and can take three forms:

- Human agents such as a benefits officer who verifies exceptions or approves payments.

- Agentic AI such as an assistant that answers questions or executes a backend system that automatically checks eligibility.

- Hybrid agents such as an immigration officer who makes final decisions but is supported by AI tools that pre-screen documents and flag anomalies.

Agents are the interface between systems and people. Their role is not just to use AI, but to guide how AI is applied: activating workflows, interpreting intent, resolving exceptions, and ensuring services follow institutional rules.

AI Blocks: Units of AI that act like callable functions.

To embed intelligence into public systems, we need units of AI that act like callable functions or tools13. In the DPI-AI Framework these units are AI Blocks.

These blocks follow the same logic as DPI components. AI Blocks are discrete, auditable modules that encapsulate a single capability. Each one can be invoked by a Public Agent or by another system, much like a function call. Public Agents can also invoke full DPI Workflows, not only individual Blocks. This creates two levels of action. First, an agent can call a specific function, such as translation or eligibility verification. Second, the agent can invoke a workflow that sequences multiple functions into a complete service.

AI Blocks are defined by the function they expose, the interface through which they are invoked, and the governance conditions under which they operate, rather than by the internal technologies they use. In practice, many AI Blocks will be hybrid implementations that combine rules-based logic, deterministic checks, data integrations, and machine learning models. Whether or not a block uses AI internally does not change its role within a DPI Workflow. What matters is how it can be composed, audited, replaced, and governed as part of a public system.

Think in terms of ingredients and recipes. AI Blocks are the ingredients. DPI Workflows are the recipes that combine ingredients with policy and process to deliver a service. Ingredients remain reusable across many recipes. Recipes remain transparent, auditable, and easy to revise as rules and needs evolve.

An AI Block has four properties that mirror DPI principles:

- Minimalist. One clear purpose with a bounded interface.

- Composable. Designed to interoperate with other Blocks and with workflow engines through open APIs and common data formats.

- Reusable. Applicable across agencies, sectors, and regions without rework.

- Governable. Observable, testable, and aligned with policy, with built in audit trails and privacy controls.

Interoperability Example: Model Context Protocol (MCP)

As AI Blocks evolve into reusable and modular capabilities, a key requirement is a common way for these systems to exchange context and interact safely. Emerging open standards such as the Model Context Protocol (MCP)14 illustrate how this interoperability can be achieved. MCP defines a lightweight protocol that allows AI systems to access external data, tools, and services while maintaining contextual integrity and auditability.

Within the DPI–AI Framework, mechanisms inspired by MCP could enable AI Blocks to communicate and collaborate through shared context layers, similar to how APIs enable interaction across other DPI building blocks. Such standards are not part of DPI workflows themselves, but they follow the same architectural principles of openness, modularity, and federated interoperability that underpin digital public infrastructure. Aligning with open protocols like MCP can help governments ensure that AI capabilities remain composable, transparent, and portable across ecosystems.

Classifying AI Blocks: Mapping AI Capabilities into a DPI Stack

AI Blocks can be classified into two main categories: Foundational and Sector Specific.

Foundational AI Blocks are general-purpose capabilities that can be reused across many sectors and services. They provide the baseline tools, the multimodal and local language primitives that are prerequisites for an inclusive and AI-ready nation. Examples include:

- Translation and transliteration into local languages

- Speech-to-text and text-to-speech

- Optical character recognition

- Text summarisation

- Image and video recognition

These blocks form a shared public kit that any sector can use, ensuring inclusion by enabling multimodal and local-language access.

Sector Specific AI Blocks are tailored to specific sectors or workflows. They embed policy and operational logic from a particular domain into callable functions that serve public mandates. Examples include:

- Eligibility verification for social protection programs

- Identity verification integrated with the digital ID platform

- Vaccine certificate validation in health services

- Clinical decision support in hospitals

- Personalized tutoring support in education

Foundational and Sector Specific blocks are complementary. Foundational blocks provide the universal primitives that ensure accessibility and reuse, while Sector Specific blocks extend them to meet the needs of specific programs and workflows. For instance, a speech-to-text block (foundational) may enable voice access, while a grievance filing block (sector specific) interprets the speech and routes it into a social protection workflow.

AI Blocks themselves can also be considered a form of Digital Public Good when they are open, reusable, and governed with policy guardrails, just as existing DPGs such as MOSIP or DHIS2 can adapt into callable AI Blocks that plug directly into workflows. This reciprocity makes intelligence a core building block of digital public infrastructure, alongside identity, payments, and data exchange.

Just as DPI created shared rails for identity and payments, AI Blocks can contribute to a shared layer of AI-Enabled Public Services that is inclusive, composable, and sovereign. Their true value emerges when Foundational and Sector Specific blocks are orchestrated together into workflows that deliver tangible outcomes for citizens with transparency and accountability.

Safeguards as Callable AI Blocks

Most DPI safeguard frameworks, such as the Universal DPI Safeguards Framework15, set out principles and recommended practices to ensure digital infrastructure is safe, inclusive, accountable, and rights-respecting throughout its life cycle. These safeguards span risk mitigation, governance, inclusion, and technical robustness across stages like strategy, design, development, deployment, and operations.

An actionable provocation is to imagine these safeguards not only as policy guidance, but as callable Foundational AI Blocks within DPI ecosystems. A Safeguards AI Block could encapsulate specific checks, validations, and compliance tests derived from the framework’s principles and associated practices, making them reusable and interoperable across agents and workflows worldwide.

For example, such an AI Block might:

- Assess and flag potential rights and safety risks in a dataset or model output before use in a public service

- Verify that AI workflows meet defined principles of inclusion and non-discrimination as set out in the safeguards framework

- Generate audit records or compliance reports that document alignment with governance expectations

- Output recommendations or constraints when running in a DPI Workflow’s strategy, design, or operations phase

By making safeguard logic callable, governments and ecosystem actors could weave shared risk mitigation and rights protection functions directly into AI workflows and Public Agents. This doesn’t centralize control or enforce one model on the world. Instead, it turns global guidance into interoperable infrastructure that supports contextual policy choices, local governance, and consistent operational signals about safety and inclusion across implementations.

Such a callable Safeguards AI Block could help balance interoperability and sovereignty by allowing local configurations and thresholds while preserving a common, machine-processable interpretation of globally recognised DPI safeguard principles.

DPI Workflows: The Orchestration Layer

While AI Blocks provide the modular capabilities, what turns them into usable public services is how they are orchestrated. This is the role of DPI Workflows, which function as structured, auditable recipes for service delivery. They connect Public Agents, AI Blocks, and core infrastructure such as digital identity, payments, and data exchange into coherent flows.

Each workflow defines a clear sequence of steps, along with the data, conditions, and safeguards that guide how a service is delivered. For example, a social protection public agent may invoke a workflow that verifies identity, checks eligibility through an AI Block, and initiates a payment using a government payment rail. These actions follow a formal structure that ensures transparency, traceability, and alignment with public policy.

Workflows can also include workflow-specific Public Agents that perform specialized tasks inside the flow. Examples include a subsidy-disbursement Public Agent embedded in a payment workflow, a school-enrollment Public Agent in education, or a vaccination-credential Public Agent in health. These workflow Public Agents operate as contextual AI Blocks that plug into larger orchestrations, enabling governments to target complex problems with precision while retaining modularity.

Just as importantly, DPI Workflows can themselves become reusable assets. A workflow that chains together identity verification, eligibility determination, and payments is not only a service but also a sharable recipe. Published in open repositories, such workflows could be adapted and reused by other governments or agencies, much like open-source code or containerized applications. Treating workflows as templates allows countries to borrow from each other’s playbooks, install them with minimal effort, and adapt them to local policies and contexts.

DPI Workflows are therefore more than technical connectors. They represent the logic of coordination, the structure that enables diverse components such as Digital Public Goods, AI Blocks, and legacy systems to operate together with consistency and oversight. This modular approach makes public systems more resilient, auditable, and adaptable to local contexts.

Inclusion is a central outcome of workflows. By embedding Foundational AI Blocks like voice-first conversational flows, multilingual translation, and accessibility features directly into orchestration, workflows allow citizens with limited literacy or connectivity to access public services on equal terms. Trust, security, privacy and safeguards are built in at the workflow level, ensuring that orchestrated intelligence operates within institutional rules and protects citizens by design.

| Generic DPI Workflow Template (YAML) workflow: id: “<workflow_id>” version: “0.1.0” description: “<short_description>” domain: “<sector_or_service_area>” governance: owner_agency: “<agency_name>” legal_basis: “<policy_or_regulation_reference>” audit_logging: true human_oversight: required: true escalation_to: “<role_or_unit>” retention_policy: “<e.g., 5y>” accountability_note: “Public Agents orchestrate steps; institutional authority remains with government.” actors: public_agent: id: “<public_agent_id>” channels: [“web”, “mobile”, “whatsapp”, “voice”] languages: [“<lang_1>”, “<lang_2>”] human_agent: id: “<human_agent_id>” role: “<caseworker_or_officer_role>” inputs: requester: identifier: { type: string, required: true } consent_token: { type: string, required: true } request: payload: { type: object, required: true } attachments: { type: array, required: false } ai_blocks: – name: “<ai_block_name>” kind: “foundational | sector_specific” interface: “<callable_function_name()>” io: in: [“<input_ref_1>”, “<input_ref_2>”] out: [“<output_ref_1>”, “<output_ref_2>”] governance: purpose: “<purpose_limitation>” data_minimization: true logging: true fallback: “<fallback_action>” safeguards: enabled: true callable_ai_block: “<safeguards_ai_block_name()>” checks: – “consent_present” – “purpose_limitation” – “data_minimization” – “non_discrimination” – “explainability_ready” on_failure: action: “escalate” to: “<human_agent_id>” citizen_message: “<plain_language_message>” steps: – id: “step_1” call: “<ai_block_name>” on_success: “step_2” on_failure: action: “retry | fallback | escalate | stop” retry: { max_attempts: 3, backoff: “exponential” } to: “<human_agent_id>” citizen_message: “<plain_language_message>” – id: “step_2” call: “<ai_block_name>” condition: “<optional_boolean_expression>” on_success: “step_3” on_failure: action: “escalate” to: “<human_agent_id>” citizen_message: “<plain_language_message>” outputs: status: “<success | failed | escalated>” decision: “<optional_decision_object>” audit_trail_ref: “<log_reference>” logging: events: – “workflow_started” – “ai_block_called” – “safeguards_checked” – “decision_made” – “escalation_triggered” – “workflow_completed” redaction: pii_fields: [“requester.identifier”, “requester.consent_token”] |

Public Agents: AI-enabled assistants for the public sector

Small Language Models (SLM) (or Large Language Models depending on scale, budget or context), optimized for efficiency and contextual relevance, can be deployed within ministries, municipal offices, or service centers. When coupled with DPI, they power the creation of Public Agents.

Public Agents are AI-enabled assistants that may take the form of software-based agents, AI-assisted public servants, or hybrid arrangements combining both. They interact with citizens, officials, or service providers within defined rights-based boundaries, and activate DPI Workflows that orchestrate the use of AI Blocks to complete specific tasks. In all cases, Public Agents are not autonomous actors but accountable extensions of government capacity, ensuring that interactions remain auditable and aligned with public governance.

In practice, Public Agents use the language and reasoning capabilities of SLMs to help interpret intent, structure requests, and guide workflows. Where appropriate, these capabilities may support human decision-makers rather than replace them. The Public Agent coordinates which AI Blocks are invoked and how the workflow proceeds, enabling bounded functions such as guiding an enrolment, validating a document, or initiating a transaction.

Public Agents can support tasks such as:

- Act as on-demand experts, embedded in messaging platforms, web portals or mobile apps.

- Handle citizen queries using publicly governed AI blocks such as eligibility verification, grievance filing, or identity assistance.

- Operate in low-resource or multilingual environments, using lightweight language models adapted with local data and civic logic.

In some cases, Public Agents may also be specialized for a single function within a workflow, such as verifying eligibility against registries or validating submitted documents. These remain callable, modular units aligned with DPI, complementing foundational AI Blocks without requiring full retraining.

As these modular capabilities mature, there is a natural progression toward multi-agent orchestration16. This refers to multiple agents collaborating by sharing context, coordinating across workflows, and dynamically decomposing tasks that a single agent could not achieve alone. Such architectures introduce new requirements for trust, interoperability, and accountability. DPI provides the shared digital rails to meet these requirements, offering common protocols, registries, and governance frameworks that ensure agents and workflows operate securely and transparently. Building trust in Public Agents requires transparency in their actions, clear consent mechanisms, and cultural and linguistic adaptation to local contexts.

| Generic Public Agent Spec + DPI Workflow Integration Template (YAML) public_agent: id: “<public_agent_id>” description: “<plain-language purpose>” channels: [“web”, “whatsapp”, “voice”] languages: [“<lang_1>”, “<lang_2>”] ai_model: # Plug-and-play adapter for common ecosystems adapter: “openai | anthropic | google | ollama | vllm | tgi | azure_openai | bedrock | custom” runtime: “external_api | sovereign_cloud | on_prem” # Minimal required fields (swap these to change providers) endpoint: “<base_url_or_gateway_url>” model: “<model_id_or_name>” auth_ref: “<secret_manager_key_or_env_ref>” # Optional compatibility hints (adapter maps these to provider-specific APIs) interface: “messages | chat_completions” timeout_ms: 30000 parameters: temperature: 0.2 max_tokens: 800 capabilities: – “intent_interpretation” – “workflow_selection” – “plain_language_explanations” constraints: – “no_final_decisions_outside_workflows” – “no_data_access_without_consent” – “allow_only_listed_workflows” permissions: can_invoke_workflows: – “<workflow_id_1>” – “<workflow_id_2>” can_call_ai_blocks_directly: false required_context: identity: required: true fields: [“requester.identifier”] consent: required: true fields: [“requester.consent_token”] workflow_invocation: engine_endpoint: “<workflow_engine_url>” mode: “invoke_by_id” request_shape: workflow_id: “<string>” inputs: “<object>” context: identity: “<object>” consent: “<object>” response_shape: status: “<success | failed | escalated>” decision: “<object>” explanation: “<string>” audit_trail_ref: “<string>” runtime_behavior: intent_to_workflow_mapping: method: “rules_then_model” allow_only_listed_workflows: true escalation: on: [“safeguards_failure”, “risk_flag”, “low_confidence”, “appeal_requested”] to_human_agent: “<human_agent_id>” logging: audit_logging: true redact_fields: [“requester.identifier”, “requester.consent_token”] |

Architecture Principles and Design Patterns of the DPI–AI Framework

The DPI–AI Framework builds on and extends the DPI Tech Architecture Principles17 into the domain of AI-Enabled Public Services. The same design logics that allowed digital identity, payments, and data exchange to scale inclusively now guide the creation of AI Blocks, DPI Workflows, and Public Agents. Together, these elements form the programmable core of AI-ready digital public infrastructure. To support both durable governance and practical implementation, the framework distinguishes between Principles and Patterns. Together, they provide a foundation for governments to design, govern, and evolve AI-Enabled Public Services that are open, modular, and trustworthy.

Principles: The “Why” — Governance and Philosophy

Principles define the enduring foundations of the DPI–AI Framework. They express the values and governance logics that guide how systems should be designed and deployed, regardless of technology or context. These are the non-negotiable elements that ensure AI-enabled public services remain sovereign, inclusive, and accountable. Principles answer the “why” behind the architecture: why we prioritize openness over control, reuse over reinvention, and public purpose over private optimization.

- Interoperability and Portability over Lock-In: AI Blocks and DPI Workflows, should be (when possible) model-, cloud- and vendor-agnostic. They should operate through open APIs and shared protocols, ensuring portability across cloud providers, model architectures, and hosting environments. This prevents dependency on a single vendor, enables hybrid deployments, and safeguards sovereign control over national digital systems.

- Minimalism: Each AI Block, DPI Workflow, or Agent should have a single, well-defined purpose with a bounded interface. By avoiding over-specification and monolithic designs, minimalism keeps intelligence auditable, reduces complexity, and ensures components remain reusable and evolvable as new technologies and policies emerge.

- Inclusion by Design: AI-Enabled Public Services must expand access, not reinforce exclusion. Foundational AI Blocks for voice, translation, transcription, image recognition and accessibility are prerequisites. Workflows should embed voice-first and multilingual interaction, and Agents should be designed to serve citizens with low literacy or connectivity.

- Sovereign by Design: Sovereignty is not just about where data is stored, but about maintaining the agency and capacity to shape digital futures by design18. Countries should embed local policy logic, data governance, and cultural norms into AI Blocks, Workflows, and Public Agents, while building the institutional competence to make strategic choices about technology dependencies. Sovereignty in DPI-AI means retaining control, understanding the options and costs of changing solution or supplier to avoid a lock-in, and ensuring that digital systems serve national priorities while enabling informed collaboration with global ecosystems.

- Security and Privacy by Design: AI Blocks, Workflows, and Agents should all emit auditable logs, respect consent, and preserve rights. Bias detection, explainability, and oversight are embedded by default, ensuring that intelligence strengthens public trust.

- AI as an Enabler, Not a Replacement: AI systems are augmentative tools. They support tasks such as classification, summarization, executions and translation within DPI domains, they execute human judgment but they do not replace institutional accountability. Their role is functional and bounded, not autonomous. Safeguards and Ethical Oversight: Every AI Block, Workflow, and Agent must comply with ethical, legal, and institutional safeguards, ensuring transparency, explainability, and auditability in all decision-making processes.

Patterns: The “How” — Technical and Operational Application

Patterns describe how the principles are translated into practice. They capture the repeatable methods and design approaches that make the framework real in implementation. While principles remain constant, patterns evolve with technology, institutional maturity, and local context. They guide the “how”: how modular systems are composed, how interoperability is achieved, and how collaboration between public and private actors is structured to align with shared goals.

- Modularity: AI Blocks, DPI Workflows, and Public Agents should be composable into larger systems through APIs and shared specifications. Agents themselves should also be able to interoperate and combine with other agents, enabling multi-agent orchestration. This modularity supports incremental upgrades, cross-sector reuse, and local adaptation without requiring full infrastructure overhauls.

- Federated by Design: DPI-AI systems should avoid centralization when possible. AI Blocks, DPI Workflows, and Public Agents must be designed for federated deployment across multiple government agencies, subnational organizations, and ecosystem actors. Based on the principle of modularity, each component should remain independently deployable while interoperating through shared standards. This ensures resilience, distributed control, and interoperability without creating single points of failure.

- Efficiency through Reuse: Foundational AI Blocks, workflow templates, and reusable agent skills should be deployed once and reused across sectors. This reduces duplication, accelerates scaling, and creates economies of scale, particularly for resource-constrained governments.

- Structured Public–Private Collaboration: Governments set the guardrails (specifications, standards, interfaces, and governance protocols) within which the private sector and civic innovators can build. This applies to Blocks, Workflows, and Agents alike, ensuring innovation is aligned with public purpose while leveraging market energy.

- Regional Alignment and Cross-Border Integration: Regional digital integration should be built on interoperable, federated systems that enable cross-border collaboration without centralising control. By aligning standards, governance approaches, and technical architectures, countries can create shared digital corridors across identity, payments, and data exchange while preserving national sovereignty. Modular and interoperable designs support responsible scaling, fiscal sustainability, and the gradual emergence of AI-ready regional digital ecosystems.

- Workflow-Centric Service Delivery: The unit of delivery in the DPI-AI Framework is the DPI Workflow. AI Blocks provide callable functions, Public Agents activate them, and DPI rails ensure trusted data and identity. Together they form auditable processes that deliver real services with clear guardrails and accountability.

- Orchestratable by Design: AI Blocks, DPI Workflows, and Public Agents should all be designed for orchestration in multi-agent ecosystems. Shared protocols enable negotiation, delegation, and task completion across domains. By operating within DPI Workflows, these orchestrations remain modular, auditable, and rights-preserving.

Seen through this structure, the DPI–AI Framework reimagines the idea of the digital stack itself. Instead of a static service layer, workflows become the programmable core that composes AI Blocks, DPI Workflows and activates them through Agents, whether human or automated. Public service delivery evolves from a fixed layer into a dynamic set of orchestrated flows that are intelligent, modular, and governed in the public interest.The figure below, adapted from the original stack model by PlatformLand Project (led by Richard Pope)19, then adapted to DPI by David Eaves and UCL20 illustrates this shift: showing how AI Blocks, DPI workflows and Public Agents sit at the top of the architecture, transforming digital infrastructure into living, adaptive AI-Enabled Public Services.

From Digital Public Goods to AI Blocks: Expanding the DPG Ecosystem

Digital Public Goods (DPGs)21 have catalyzed the growth of Digital Public Infrastructure by providing open-source software, open standards, open data, open AI systems, and open content collections that adhere to privacy and other applicable laws and best practices, do no harm, and help attain the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

In the context of AI-enhanced governance, we propose to treat: DPGs as Sector Specific AI Blocks, supported by their existing APIs and microservices architecture. The true value emerges when AI Blocks and DPGs are orchestrated through DPI Workflows and invoked by Public Agents. A DPI workflow might combine identity verification, eligibility assessment, payment instruction, and notification into a single auditable pathway, while a Public Agent interprets citizen intent and activates the right sequence of functions.

By reframing DPGs as callable infrastructure, governments gain responsiveness and modularity. AI Blocks, acting as tools for Public Agents, can be dynamically invoked through workflows without retraining or redesign. This preserves the openness and public ownership of DPGs while extending their utility into the AI layer of digital infrastructure. Sustaining open-source AI Blocks requires clear funding models, community governance, and international collaboration through open repositories like the Digital Public Goods Alliance Registry22.

DPGs projects as AI Blocks: Tools for Public Agents

To illustrate this modular shift, we can treat existing DPGs as Sector Specific AI Blocks, part of DPI Workflows or invoked by Public Agents. Each function exposes a specific, auditable capability that can be composed with others to form complete services:

- MOSIP exposes enroll_identity() to support digital ID registration guidance.

- OpenCRVS becomes register_birth(), triggering civil registration workflows.

- OpenSPP offers check_benefit_eligibility() for social protection assessments.

- OpenFn exposes instantiate_workflow(wf_id) to allow an AI agent to start a specific DPI workflow.

- Mifos provides get_credit_profile() for inclusive finance use cases.

- Mojaloop supports transfer_funds() within secure, interoperable payment networks.

- X-Road offers fetch_verified_record() to retrieve authenticated public data.

- Inji or Diia act as credentialing endpoints, such as issue_credential() or verify_identity() using verifiable credential wallets.

Alongside these, Foundational AI Blocks expose intelligence functions in the same callable manner:

- classify_document() for automated document review.

- summarize_case_file() for grievance handling.

- translate_local_language() for multilingual service delivery.

- detect_anomaly() for fraud or error prevention.

When connected through DPI Workflows, these callable functions form auditable service pathways. For example, a human agent assisting a citizen can invoke verify_identity() via MOSIP, check_benefit_eligibility() via OpenSPP, and then transfer_funds() through Mojaloop, while an AI Block provides a plain-language explanation of the outcome.

This approach reframes DPGs and AI Blocks as interoperable, callable components that can be dynamically assembled by Public Agents and orchestrated through DPI Workflows. In doing so, they become infrastructure-native services: discoverable, composable, and adaptable across jurisdictions.

The shift also presents challenges. Existing DPG projects must evolve from vertically integrated platforms to modular, workflow-ready functions, requiring new design and business models. At the same time, this opens opportunities: callable infrastructure can embed directly into governance and service delivery, and new funding models tied to usage and ecosystem value can strengthen sustainability while keeping DPGs open, trusted, and globally interoperable.

Use Cases: Making the Vision Tangible

To illustrate how the DPI–AI Framework can be applied in practice, this section presents a set of representative use case archetypes rather than an exhaustive list of examples. These archetypes show how AI Blocks, and DPI Workflows can be combined in repeatable patterns across sectors and regions. Each example demonstrates how governments can extend functionality incrementally while preserving transparency, sovereignty, and accountability.

Across all cases, a Public Agent, human, digital, or hybrid, interprets intent, activates a DPI Workflow, and orchestrates the invocation of sector specific and foundational AI Blocks. Workflows typically combine DPI rails such as identity, data exchange, or payments with callable DPG functions and AI Blocks, enabling solutions that are adaptable to local contexts and scalable across infrastructure.

Access to Social Services and Benefits

Archetype: Guided enrollment, eligibility verification, and benefit delivery

Integrated Social Support Assistant: A multilingual public agent helps individuals enroll in digital identity systems, check eligibility for social or health benefits, and receive fund transfers. The workflow invokes identity enrollment, benefit eligibility verification, and payment disbursement functions, supported by foundational AI Blocks for safeguards that validate consent, inclusion, and appropriate use before funds are released.

Health Benefit Screener: A citizen-facing agent guides users through health benefit eligibility and claims processes. The workflow invokes health eligibility checks and insurance or reimbursement functions, with foundational AI Blocks for safeguards supporting privacy protection, explainability of outcomes, and access to grievance mechanisms.

Civil Registration, Legal, and Administrative Services

Archetype: Assisted navigation of formal processes using trusted records

Multilingual Civic Registration Assistant: A public agent supports individuals in registering life events such as births or deaths through a workflow that invokes civil registration functions and verified record retrieval via data exchange. Foundational AI Blocks for safeguards support non-discrimination, accessibility, and lawful data use.

Legal and Administrative Guidance Agent: A localized agent helps individuals understand land, legal, or administrative procedures by invoking record lookup and document generation functions, combined with foundational AI Blocks for translation, summarisation, and safeguards that help surface potential rights or exclusion risks.

Livelihoods, Employment, and Economic Participation

Archetype: Decision support and access to economic opportunities

Agricultural and Livelihood Support Assistant: An advisory agent supports farmers or informal workers by orchestrating credit profiling, weather or market information, and sector-specific recommendations. Foundational AI Blocks for safeguards help validate fairness, relevance, and appropriateness of recommendations.

Employment and Skills Matchmaking Agent: A job support agent verifies credentials, matches individuals to employment opportunities, and recommends skills development pathways. Foundational AI Blocks for safeguards support transparency, consent, and bias awareness in matching and recommendation logic.

Education, Information, and Human Development

Archetype: Personalized and inclusive access to public information

Digital Learning Assistant: A learning agent fetches educational content, adapts it to individual learning levels, and translates material into local languages. Foundational AI Blocks for safeguards support age-appropriateness, inclusion, and explainability.

Multilingual Civic Information Agent: A public-facing agent answers citizen queries across service portals, messaging platforms, or voice channels by invoking publicly governed AI Blocks. Foundational AI Blocks for safeguards support accuracy, neutrality, and accessible communication.

Crisis Response and Urban Services

Archetype: Coordinated, time-sensitive orchestration across systems

Disaster Response Coordination Agent: A coordination agent identifies affected populations, maps risk or impact zones, and dispatches relief or support requests. Foundational AI Blocks for safeguards support accountable prioritization, traceability, and oversight under emergency conditions.

Urban Mobility and Service Assistant: A commuter or urban services agent plans routes, checks service availability or fares, and processes payments. Foundational AI Blocks for safeguards support transparency, equitable access, and clear communication of options and constraints.

These examples are not applications in the traditional sense. They represent theoretical conversational Public Agents that dynamically invoke DPI functions, Digital Public Goods, sector-specific AI Blocks, and foundational AI Blocks through workflows. The emphasis is on reusable patterns that can be adapted across sectors, regions, and institutional contexts.

Challenges Ahead: Safeguards, Procurement & Governance

The modular vision is powerful, but realizing it at scale depends on overcoming key institutional and ecosystem barriers. While the technological landscape for AI and DPI is advancing rapidly, the primary bottlenecks lie not in capability but in procurement, governance, and operational design. The DPI-AI Framework offers a pathway to embed intelligence into digital systems through modular, rights-based design, but scaling this vision requires addressing deep institutional constraints.

Across DPI workflows such as eligibility determination, consent orchestration, document translation, or benefits targeting, AI Blocks are already emerging as composable building blocks. Yet the systems that support them remain misaligned. To operationalize and scale the framework responsibly, governments and development partners must align their strategies with universal safeguards for human rights, equity, and transparency. These challenges emerge as key things to be addressed by the ecosystem:

- Outcome-Oriented, Rights-Based Procurement: Procurement frameworks must evolve from static deliverables to outcome-driven models tailored to specific public functions such as translate document, predict eligibility, or flag anomaly. Safeguards including data protection, explainability, and accessibility must be embedded from the outset. Agile instruments such as open frameworks and milestone-based contracting can help match the pace of AI innovation while preserving accountability.

- Verification and Certification of AI Blocks: As AI Blocks become modular, callable components reused across public workflows, ensuring their safety and integrity becomes a critical challenge. Governments may increasingly depend on third-party foundational and sector-specific AI Blocks, creating risks of integrating malicious or compromised components that could enable identity theft, fraud, impersonation, or other harms amplified by AI-driven automation.

This raises unresolved questions about verification and certification. Unlike traditional software, AI Blocks can change behaviour over time, making one-time approval insufficient. Clear responsibility is needed for who validates AI Blocks, against what criteria, and with what ongoing oversight. Whether this role should be performed by governments, independent bodies, or ecosystem actors such as Digital Public Goods Alliance remains open, but addressing it will be essential to maintain security, trust, and accountability in AI-enabled public infrastructure.

- Utility-Based Pricing and Interoperable Licensing: Public workflows such as KYC or document verification may invoke AI functions thousands of times per day. Usage-based pricing tied to service units, rather than bundled licenses, can reduce vendor dependence and improve fiscal planning. Equitable access for low-income countries requires royalty-free or tiered / dynamic pricing aligned with open norms.

- AI-Ready Financing from Development Banks: Multilateral development banks must recognize AI as a core layer of digital public infrastructure, not a peripheral add-on. Financing instruments should support co-development, conditional disbursements on open standards adoption, and invest in national capacity for auditing, safeguards, and ethical implementation.

- Institutional and Ecosystem Capacity Building: Governments must invest in governance capacity to design, deploy, and adapt AI-enabled infrastructure. This includes training civil servants, creating data governance units, and supporting local developers. Capacity must extend to inclusion practices such as voice-first and multilingual interfaces that ensure underserved groups are reached.

- Monitoring and Evaluation: The absence of shared metrics and evaluation frameworks makes it difficult for governments to benchmark progress, compare approaches, and ensure accountability in AI deployment. Greater alignment around common metrics, specifications, and standards, such as AI management systems and internationally recognised principles, would support more consistent monitoring and oversight.

- Data Governance and Digital Sovereignty: Data is the substrate of AI-Enabled Public Services, yet ownership and control are often fragmented or externalized. Sovereign data governance regimes must define access, consent, and reuse across systems. DPI primitives such as identity, registry, and consent layers must include traceability, purpose limitation, and public oversight by default.

- Transparent Governance and Independent Oversight: As AI becomes embedded in critical decisions such as citizen classification or eligibility ranking, independent oversight is essential. Legal authorities must be empowered to inspect deployments, evaluate safeguards, and publish public reports. Redress mechanisms should be available for individuals impacted by automated decisions.

- Bridging the Digital Divide and Ensuring Inclusion: Inclusion is non-negotiable. Inclusion must be embedded in every block. DPI-AI systems should offer multimodal interfaces such as voice, SMS, or offline access, and be designed for populations with low literacy, poor connectivity, or accessibility needs. User research with underserved groups should guide workflow design from the start.

- Extending Legacy Systems through a “+1” Integration Approach: Governments often operate legacy systems built and maintained over decades. Replacing them wholesale is rarely feasible. Instead, the DPI-AI Framework encourages a +1 approach, layering new capabilities alongside existing systems, enhancing them incrementally without requiring full redesign. This pragmatic strategy respects institutional realities while unlocking innovation.

- Defining Public versus Private AI Blocks: A central challenge in the DPI–AI Framework is determining which AI Blocks can be considered part of public infrastructure and which should remain private. This question is core to current debates on sovereign and public interest AI, and applies to both foundational capabilities and sector-specific AI Blocks used in public services.

While some AI capabilities may qualify as public if they are openly specified, broadly accessible, and governed with clear policy guardrails, others function as private utilities even when widely adopted. The framework therefore needs clear criteria for when public workflows can rely on private or hybrid AI Blocks, and under what conditions. Addressing this distinction is essential for sovereignty, accountability, and public trust.

Successfully addressing these challenges will determine whether DPI-AI adoption enhances trust, transparency, and inclusion, or replicates inequities at scale. A safeguards-first, modular approach ensures that governments retain control, citizens benefit directly, and innovation is channeled toward shared public purpose.

Conclusion

The next phase of digital public infrastructure will not be defined by modular components alone, but by the intelligent workflows that integrate them into adaptive systems. It is in the dynamic orchestration of these components, through DPI Workflows and Public Agents, that real public value is created.

This paper has outlined a practical vision for that future: a transition from vertically integrated Digital Public Goods to composable AI Blocks that, when orchestrated by DPI Workflows and activated by citizen-facing Agents, enable faster, fairer, and more efficient public service delivery within a rights-based architecture.

This evolution is not about simulating cognition or pursuing artificial general intelligence. It is about equipping governments with architectural tools to modernize public services incrementally, using reusable, transparent, and purpose-built components. The DPI–AI Framework demonstrates how this can be achieved by placing modularity, local adaptability, and public governance at the center of digital transformation.

Governments do not need to build end-to-end AI systems. They need to build interfaces between intelligence and infrastructure, bridges that allow AI to serve public needs while preserving control, equity, and trust. That means:

- Designing AI as infrastructure, not as opaque platforms.

- Treating Digital Public Goods as composable assets, not as static solutions.

- Integrating intelligence gradually, as DPI integrated identity, payments, and data into a shared stack.

The real opportunity lies not in centralizing intelligence, but in distributing it. AI Blocks should be usable across systems, contexts, and communities. Each Block must serve a public function, provide transparency, and remain accountable to public institutions. Just as APIs enabled interoperability in earlier generations of digital infrastructure, emerging open standards such as Model Context Protocols (MCPs) now make it possible for AI systems to interconnect through shared context layers. These protocols extend the logic of DPI by ensuring openness, modularity, and auditability within AI environments, allowing distributed intelligence to function as a coherent public system. With the right design principles, this intelligence becomes a durable public asset rather than a private service.

DPI Workflows can make this vision tangible by becoming sharable recipes for service delivery. A workflow that chains together identity verification, eligibility determination, and payments can be published, adapted, and reused by other governments or agencies, much like open-source code on GitHub or containerized applications shared through Docker. By treating workflows as reusable templates, countries can borrow from each other’s playbooks, install them with minimal effort, and adapt them to local policies and contexts.

This portability transforms AI-Enabled Public Services into a global commons of practice. Instead of reinventing solutions in silos, governments can access catalogs of pre-built workflows and Blocks, remix them for their own needs, and share improvements back into the ecosystem. In the same way that open-source software accelerated private innovation, open repositories of AI Blocks and DPI Workflows can accelerate public innovation, ensuring that solutions scale faster, cost less, and remain accountable to shared public values.If DPI was the foundation, AI blocks, DPI Workflows, and Agents are the scaffolding for what comes next. They provide a modular, flexible, and accountable way to deliver smarter services, faster responses, and broader inclusion. The work ahead is not about scaling AI; it is about shaping it to serve the public stack and to strengthen the capacity of governments to act with intelligence, transparency, and purpose.

How to cite

CDPI Abadie, D. (2026). DPI-AI Framework: Building AI-Ready Nations through Digital Public Infrastructure. https://digitalpublicinfrastructure.ai

- The Matrix https://www.imdb.com/es/title/tt0133093/?ref_=ls_t_1 ↩︎

- Small Language Models are the Future of Agentic AI https://arxiv.org/abs/2506.02153 ↩︎

- Public Digital – Our view on digital sovereignty https://public.digital/pd-insights/blog/2025/07/our-view-on-digital-sovereignty ↩︎

- CDPI Wiki – What is DPI? https://docs.cdpi.dev/the-dpi-wiki/what-is-dpi ↩︎

- CDPI – DPI Overview https://docs.cdpi.dev/the-dpi-wiki/dpi-overview ↩︎

- Global State of DPI (Oct 2024). Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose, UCL. https://dpimap.org/ ↩︎

- Towards Best Practices for Open Datasets for LLM Training arXiv:2501.08365 ↩︎

- Using Large Language Models responsibly in the civil service: a guide to implementation https://www.bennettschool.cam.ac.uk/publications/using-llms-responsibly-in-the-civil-service/ ↩︎

- European Data Protection Supervisor – Large language models (LLM) https://www.edps.europa.eu/data-protection/technology-monitoring/techsonar/large-language-models-llm_en ↩︎

- University College London. Interactions Between Artificial Intelligence and Digital Public Infrastructure. arXiv:2412.05761 ↩︎

- Next Generation Digital Government Architecture – Kristo Vaher https://docs.google.com/document/d/1UJ-5wi9wavWzA2n4LhsbONJqdxjUSIgMxKJNaZZslas/edit?tab=t.0#heading=h.xwh5d5zd5889 ↩︎

- Digital Public Goods Alliance – DPG https://www.digitalpublicgoods.net/digital-public-goods ↩︎

- Practices for Governing Agentic AI Systems https://openai.com/index/practices-for-governing-agentic-ai-systems/ ↩︎

- Model Context Protocol (MCP) https://modelcontextprotocol.io/docs/getting-started/intro ↩︎

- The Universal DPI Safeguards Framework https://www.dpi-safeguards.org/ ↩︎

- AI Agents vs. Agentic AI: A Conceptual Taxonomy, Applications and Challenges arXiv:2505.10468 [cs.AI] https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2505.10468 ↩︎

- CDPI DPI Tech Architecture Principles https://docs.cdpi.dev/the-dpi-wiki/dpi-tech-architecture-principles ↩︎

- Public Digital – Our view on digital sovereignty https://public.digital/pd-insights/blog/2025/07/our-view-on-digital-sovereignty ↩︎

- Platform Land was a project led by Richard Pope https://www.platformland.org/ https://www.platformland.xyz/ ↩︎

- Eaves, D., Mazzucato, M. and Vasconcellos, B. (2024). Digital public infrastructure and public value: What is ‘public’ about DPI ? UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose, Working. Paper Series (IIPP WP 2024-05). Available at: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/bartlett/public-purpose/wp2024-05 ↩︎

- DPGA – Digital Public Goods https://www.digitalpublicgoods.net/digital-public-goods ↩︎

- DPGA Registry – https://www.digitalpublicgoods.net/registry ↩︎